在本篇文章中,我们学习一下函数式编程的中非常重要的Map、Reduce、Filter的三种操作,这三种操作可以让我们非常方便灵活地进行一些数据处理——我们的程序中大多数情况下都是在到倒腾数据,尤其对于一些需要统计的业务场景,Map/Reduce/Filter是非常通用的玩法。下面先来看几个例子:

基本示例

Map示例

下面的程序代码中,我们写了两个Map函数,这两个函数需要两个参数,

- 一个是字符串数组

[]string,说明需要处理的数据一个字符串 - 另一个是一个函数

func(s string) string或func(s string) int

func MapStrToStr(arr []string, fn func(s string) string) []string {

var newArray = []string{}

for _, it := range arr {

newArray = append(newArray, fn(it))

}

return newArray

}

func MapStrToInt(arr []string, fn func(s string) int) []int {

var newArray = []int{}

for _, it := range arr {

newArray = append(newArray, fn(it))

}

return newArray

}

整个Map函数运行逻辑都很相似,函数体都是在遍历第一个参数的数组,然后,调用第二个参数的函数,然后把其值组合成另一个数组返回。

于是我们就可以这样使用这两个函数:

var list = []string{"Hao", "Chen", "MegaEase"}

x := MapStrToStr(list, func(s string) string {

return strings.ToUpper(s)

})

fmt.Printf("%v\n", x)

//["HAO", "CHEN", "MEGAEASE"]

y := MapStrToInt(list, func(s string) int {

return len(s)

})

fmt.Printf("%v\n", y)

//[3, 4, 8]

我们可以看到,我们给第一个 MapStrToStr() 传了函数做的是 转大写,于是出来的数组就成了全大写的,给MapStrToInt() 传的是算其长度,所以出来的数组是每个字符串的长度。

我们再来看一下Reduce和Filter的函数是什么样的。

Reduce:

func Reduce(arr []string, fn func(s string) int) int {

sum := 0

for _, it := range arr {

sum += fn(it)

}

return sum

}

var list = []string{"Hao", "Chen", "MegaEase"}

x := Reduce(list, func(s string) int {

return len(s)

})

fmt.Printf("%v\n", x)

// 15

Filter:

func Filter(arr []int, fn func(n int) bool) []int {

var newArray = []int{}

for _, it := range arr {

if fn(it) {

newArray = append(newArray, it)

}

}

return newArray

}

var intset = []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10}

out := Filter(intset, func(n int) bool {

return n%2 == 1

})

fmt.Printf("%v\n", out)

out = Filter(intset, func(n int) bool {

return n > 5

})

fmt.Printf("%v\n", out)

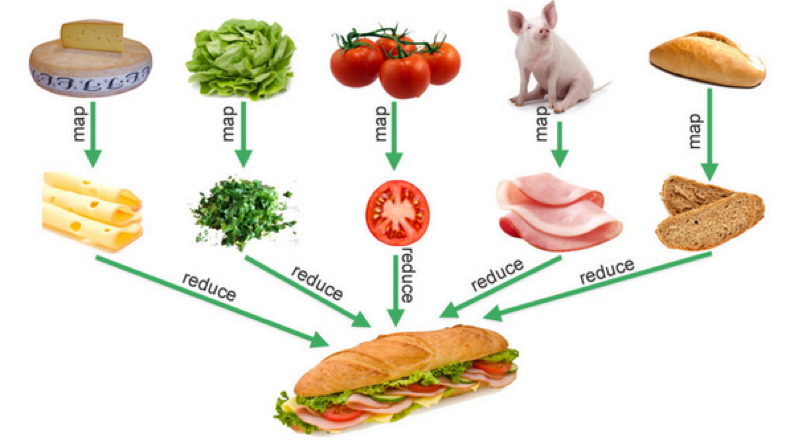

下图是一个比喻,其非常形象地说明了Map-Reduce是的业务语义,其在数据处理中非常有用。

业务示例

通过上面的一些示例,你可能有一些明白,Map/Reduce/Filter只是一种控制逻辑,真正的业务逻辑是在传给他们的数据和那个函数来定义的。是的,这是一个很经典的“业务逻辑”和“控制逻辑”分离解耦的编程模式,Golang中常用的sort包中也采用了这种设计模式实现了sort.Slice()方法。下面我们来看一个有业务意义的代码,来让大家强化理解一下什么叫“控制逻辑”与业务逻辑分离。

首先,我们定义一个员工对象,以及一些数据:

type Employee struct {

Name string

Age int

Vacation int

Salary int

}

var list = []Employee{

{"Hao", 44, 0, 8000},

{"Bob", 34, 10, 5000},

{"Alice", 23, 5, 9000},

{"Jack", 26, 0, 4000},

{"Tom", 48, 9, 7500},

{"Marry", 29, 0, 6000},

{"Mike", 32, 8, 4000},

}

然后,我们有如下的几个函数:

func EmployeeCountIf(list []Employee, fn func(e *Employee) bool) int {

count := 0

for i, _ := range list {

if fn(&list[i]) {

count += 1

}

}

return count

}

func EmployeeFilterIn(list []Employee, fn func(e *Employee) bool) []Employee {

var newList []Employee

for i, _ := range list {

if fn(&list[i]) {

newList = append(newList, list[i])

}

}

return newList

}

func EmployeeSumIf(list []Employee, fn func(e *Employee) int) int {

var sum = 0

for i, _ := range list {

sum += fn(&list[i])

}

return sum

}

简单说明一下:

EmployeeConutIf和EmployeeSumIf分别用于统满足某个条件的个数或总数。它们都是Filter + Reduce的语义。EmployeeFilterIn就是按某种条件过虑。就是Fitler的语义。

于是我们就可以有如下的代码:

1)统计有多少员工大于40岁

old := EmployeeCountIf(list, func(e *Employee) bool {

return e.Age > 40

})

fmt.Printf("old people: %d\n", old)

//old people: 2

2)统计有多少员工薪水大于6000

high_pay := EmployeeCountIf(list, func(e *Employee) bool {

return e.Salary >= 6000

})

fmt.Printf("High Salary people: %d\n", high_pay)

//High Salary people: 4

3)列出有没有休假的员工

no_vacation := EmployeeFilterIn(list, func(e *Employee) bool {

return e.Vacation == 0

})

fmt.Printf("People no vacation: %v\n", no_vacation)

//People no vacation: [{Hao 44 0 8000} {Jack 26 0 4000} {Marry 29 0 6000}]

4)统计所有员工的薪资总和

total_pay := EmployeeSumIf(list, func(e *Employee) int {

return e.Salary

})

fmt.Printf("Total Salary: %d\n", total_pay)

//Total Salary: 43500

5)统计30岁以下员工的薪资总和

younger_pay := EmployeeSumIf(list, func(e *Employee) int {

if e.Age < 30 {

return e.Salary

}

return 0

})

泛型Map-Reduce

我们可以看到,上面的Map-Reduce都因为要处理数据的类型不同而需要写出不同版本的Map-Reduce,虽然他们的代码看上去是很类似的。所以,这里就要带出来泛型编程了,目前的Go语言的泛型只能用 interface{} + reflect来完成。

下面我们来看一下一个非常简单不作任何类型检查的泛型的Map函数怎么写:

func Map(data interface{}, fn interface{}) []interface{} {

vfn := reflect.ValueOf(fn)

vdata := reflect.ValueOf(data)

result := make([]interface{}, vdata.Len())

for i := 0; i < vdata.Len(); i++ {

result[i] = vfn.Call([]reflect.Value{vdata.Index(i)})[0].Interface()

}

return result

}

上面的代码中,

- 通过

reflect.ValueOf()来获得interface{}的值,其中一个是数据vdata,另一个是函数vfn, - 然后通过

vfn.Call()方法来调用函数,通过[]refelct.Value{vdata.Index(i)}来获得数据。

于是,我们就可以有下面的代码——不同类型的数据可以使用相同逻辑的Map()代码:

square := func(x int) int {

return x * x

}

nums := []int{1, 2, 3, 4}

squared_arr := Map(nums,square)

fmt.Println(squared_arr)

//[1 4 9 16]

upcase := func(s string) string {

return strings.ToUpper(s)

}

strs := []string{"Hao", "Chen", "MegaEase"}

upstrs := Map(strs, upcase);

fmt.Println(upstrs)

//[HAO CHEN MEGAEASE]

但是因为反射是运行时的事,所以,如果类型什么出问题的话,就会有运行时的错误。

健壮版的Generic Map

所以,如果要写一个健壮的程序,对于这种用interface{} 的“过度泛型”,就需要我们自己来做类型检查。下面是一个有类型检查的Map代码(分为是否就地计算两个版本):

func Transform(slice, function interface{}) interface{} {

return transform(slice, function, false)

}

func TransformInPlace(slice, function interface{}) interface{} {

return transform(slice, function, true)

}

func transform(slice, function interface{}, inPlace bool) interface{} {

//check the <code data-enlighter-language="raw" class="EnlighterJSRAW">slice</code> type is Slice

sliceInType := reflect.ValueOf(slice)

if sliceInType.Kind() != reflect.Slice {

panic("transform: not slice")

}

//check the function signature

fn := reflect.ValueOf(function)

elemType := sliceInType.Type().Elem()

if !verifyFuncSignature(fn, elemType, nil) {

panic("trasform: function must be of type func(" + sliceInType.Type().Elem().String() + ") outputElemType")

}

sliceOutType := sliceInType

if !inPlace {

sliceOutType = reflect.MakeSlice(reflect.SliceOf(fn.Type().Out(0)), sliceInType.Len(), sliceInType.Len())

}

for i := 0; i < sliceInType.Len(); i++ {

sliceOutType.Index(i).Set(fn.Call([]reflect.Value{sliceInType.Index(i)})[0])

}

return sliceOutType.Interface()

}

func verifyFuncSignature(fn reflect.Value, types ...reflect.Type) bool {

//Check it is a funciton

if fn.Kind() != reflect.Func {

return false

}

// NumIn() - returns a function type's input parameter count.

// NumOut() - returns a function type's output parameter count.

if (fn.Type().NumIn() != len(types)-1) || (fn.Type().NumOut() != 1) {

return false

}

// In() - returns the type of a function type's i'th input parameter.

for i := 0; i < len(types)-1; i++ {

if fn.Type().In(i) != types[i] {

return false

}

}

// Out() - returns the type of a function type's i'th output parameter.

outType := types[len(types)-1]

if outType != nil && fn.Type().Out(0) != outType {

return false

}

return true

}

上面的代码一下子就复杂起来了,可见,复杂的代码都是在处理异常的地方。我不打算Walk through 所有的代码,别看代码多,但是还是可以读懂的,下面列几个代码中的要点:

- 代码中没有使用Map函数,因为和数据结构和关键有含义冲突的问题,所以使用

Transform,这个来源于 C++ STL库中的命名。 - 有两个版本的函数,一个是返回一个全新的数组 –

Transform(),一个是“就地完成” –TransformInPlace() - 在主函数中,用

Kind()方法检查了数据类型是不是 Slice,函数类型是不是Func - 检查函数的参数和返回类型是通过

verifyFuncSignature()来完成的,其中:NumIn()– 用来检查函数的“入参”-

NumOut()用来检查函数的“返回值”

- 如果需要新生成一个Slice,会使用

reflect.MakeSlice()来完成。

好了,有了上面的这段代码,我们的代码就很可以很开心的使用了:

可以用于字符串数组:

list := []string{"1", "2", "3", "4", "5", "6"}

result := Transform(list, func(a string) string{

return a +a +a

})

//{"111","222","333","444","555","666"}

可以用于整形数组:

list := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9}

TransformInPlace(list, func (a int) int {

return a*3

})

//{3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27}

可以用于结构体:

var list = []Employee{

{"Hao", 44, 0, 8000},

{"Bob", 34, 10, 5000},

{"Alice", 23, 5, 9000},

{"Jack", 26, 0, 4000},

{"Tom", 48, 9, 7500},

}

result := TransformInPlace(list, func(e Employee) Employee {

e.Salary += 1000

e.Age += 1

return e

})

同样,泛型版的 Reduce 代码如下:

func Reduce(slice, pairFunc, zero interface{}) interface{} {

sliceInType := reflect.ValueOf(slice)

if sliceInType.Kind() != reflect.Slice {

panic("reduce: wrong type, not slice")

}

len := sliceInType.Len()

if len == 0 {

return zero

} else if len == 1 {

return sliceInType.Index(0)

}

elemType := sliceInType.Type().Elem()

fn := reflect.ValueOf(pairFunc)

if !verifyFuncSignature(fn, elemType, elemType, elemType) {

t := elemType.String()

panic("reduce: function must be of type func(" + t + ", " + t + ") " + t)

}

var ins [2]reflect.Value

ins[0] = sliceInType.Index(0)

ins[1] = sliceInType.Index(1)

out := fn.Call(ins[:])[0]

for i := 2; i < len; i++ {

ins[0] = out

ins[1] = sliceInType.Index(i)

out = fn.Call(ins[:])[0]

}

return out.Interface()

}

泛型版的 Filter 代码如下:

func Filter(slice, function interface{}) interface{} {

result, _ := filter(slice, function, false)

return result

}

func FilterInPlace(slicePtr, function interface{}) {

in := reflect.ValueOf(slicePtr)

if in.Kind() != reflect.Ptr {

panic("FilterInPlace: wrong type, " +

"not a pointer to slice")

}

_, n := filter(in.Elem().Interface(), function, true)

in.Elem().SetLen(n)

}

var boolType = reflect.ValueOf(true).Type()

func filter(slice, function interface{}, inPlace bool) (interface{}, int) {

sliceInType := reflect.ValueOf(slice)

if sliceInType.Kind() != reflect.Slice {

panic("filter: wrong type, not a slice")

}

fn := reflect.ValueOf(function)

elemType := sliceInType.Type().Elem()

if !verifyFuncSignature(fn, elemType, boolType) {

panic("filter: function must be of type func(" + elemType.String() + ") bool")

}

var which []int

for i := 0; i < sliceInType.Len(); i++ {

if fn.Call([]reflect.Value{sliceInType.Index(i)})[0].Bool() {

which = append(which, i)

}

}

out := sliceInType

if !inPlace {

out = reflect.MakeSlice(sliceInType.Type(), len(which), len(which))

}

for i := range which {

out.Index(i).Set(sliceInType.Index(which[i]))

}

return out.Interface(), len(which)

}

使用反射来做这些东西,会有一个问题,那就是代码的性能会很差。所以,上面的代码不能用于你需要高性能的地方。